By Nuno Palma (2023)

Pages: 405, Final verdict: Must-read

Why do some countries become richer, and others don't? That is the question that economic historians—and not too many other people—obsess about.

Nuno Palma is one of those people. A Professor of Economics at the University of Manchester, he has dedicated his academic career to investigating why certain economies lag behind others, with a special focus on Portugal and its relative backwardness compared to the rest of Europe.

In Portuguese folklore, it is often said that Portugal lags at the tail end of the European Union because of the repressive Salazar dictatorship that governed from the 1920s until 1974. In As Causas do Atraso Português, Palma challenges that idea—and several other sacred cows—by taking a hard look at the country’s economic history and key performance indicators (KPIs) since the 1500s.

It is a terrific book, and for the first time in nine years, I am reviewing a title that, as far as I know, is not available in English.

The Gold Curse

The biggest difference between As Causas do Atraso Português and most similar works is that Palma is an economic historian, and it shows. The first nine chapters (we’ll get to the tenth in a moment) are packed with economic data, counterfactual scenarios, and quantitative evidence supporting Palma’s central claim: that Portugal’s economic backwardness can largely be traced back to the huge influx of gold from Brazil in the early 18th century.

This is the rough timeline of the gold rush:

- 1690s: Gold was discovered in Minas Gerais, Brazil, leading to a massive gold rush.

- 1700–1750: This was the peak period of gold shipments from Brazil to Portugal. By some estimates, Portugal received hundreds of tons of gold, making Lisbon one of the wealthiest cities in Europe.

- 1710s–1760s: The Portuguese Crown imposed strict taxation systems like the "Quinto" (20% tax on gold) and later the "Derrama" (extra taxes) to maximize state revenues.

- 1750s–1760s: The gold output started to decline, though shipments continued into the late 18th century.

This 'easy wealth', according to Palma, created a complacent state and enfeebled institutions. For instance, the Portuguese parliament (the “Cortes”) did not convene once during that century. Instead of investing in strong institutions and diversifying the economy, Portugal funneled Brazilian gold into luxurious Baroque architecture in Lisbon and increased imports from Britain—further entrenching Anglo-Portuguese economic dependence. In modern terms, Portugal fell into a classic resource curse.

Palma and his research collaborators have meticulously sifted through historical records—including GDP measures and election data—to bolster these arguments. This rigor makes the book both compelling and unique.

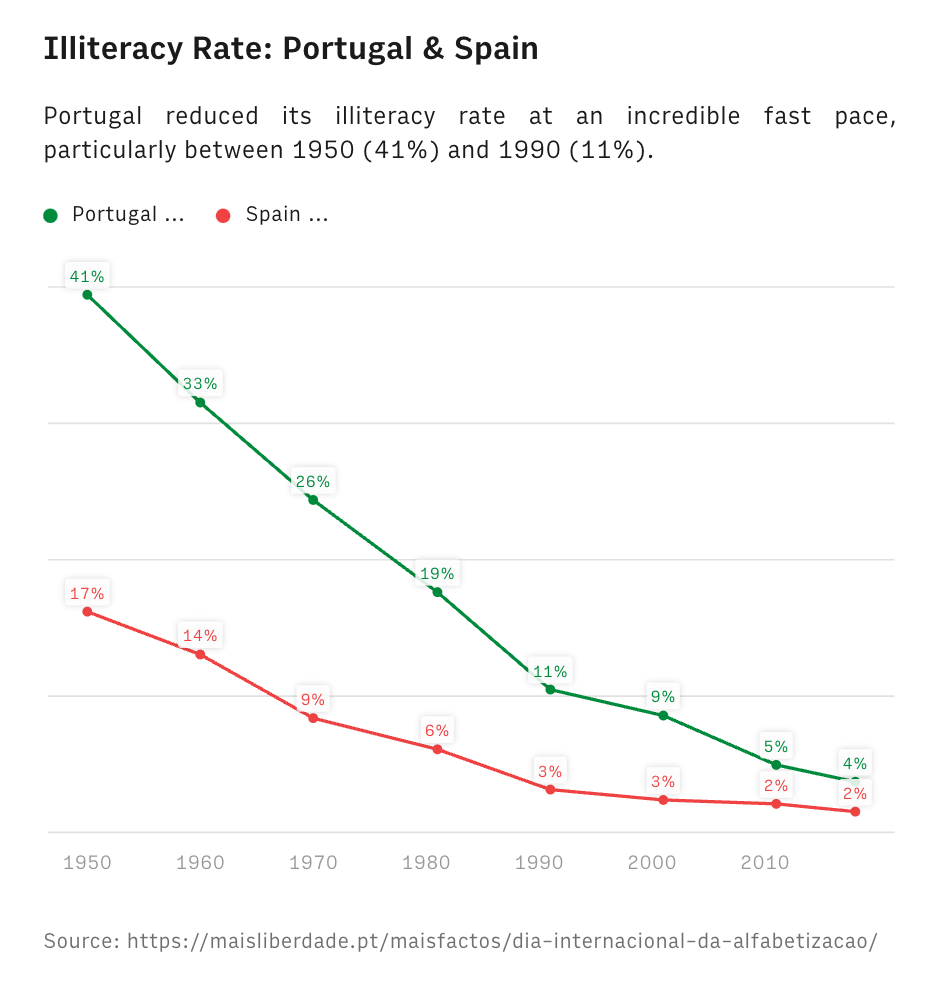

Palma applies that same rigor when discussing the Estado Novo dictatorship. Though undeniably repressive, the regime was, by many accounts, milder than other contemporary European dictatorships. The conventional wisdom in Portugal is that Salazar’s rule caused the country’s poor educational performance. Palma tells us the opposite: he shows that the literacy problem began long before the 20th century, dating back to the 18th-century expulsion of the Jesuits by the Marquis of Pombal. In fact, he shows the reader that it was under the Estado Novo that Portugal finally undertook some ambitious investments in primary education, leading to a substantial drop in illiteracy rates—though the country still trails much of Europe on this front (source, source).

My primary criticism relates to the final chapter, where Palma ventures a theory about why Portugal continues to diverge from the rest of the EU in the 21st century. He argues that the country is once again prey of a resource curse—this time, due to the constant influx of EU funds (a theory I personally sympathize with)—yet doesn't offer much hard evidence to substantiate it.

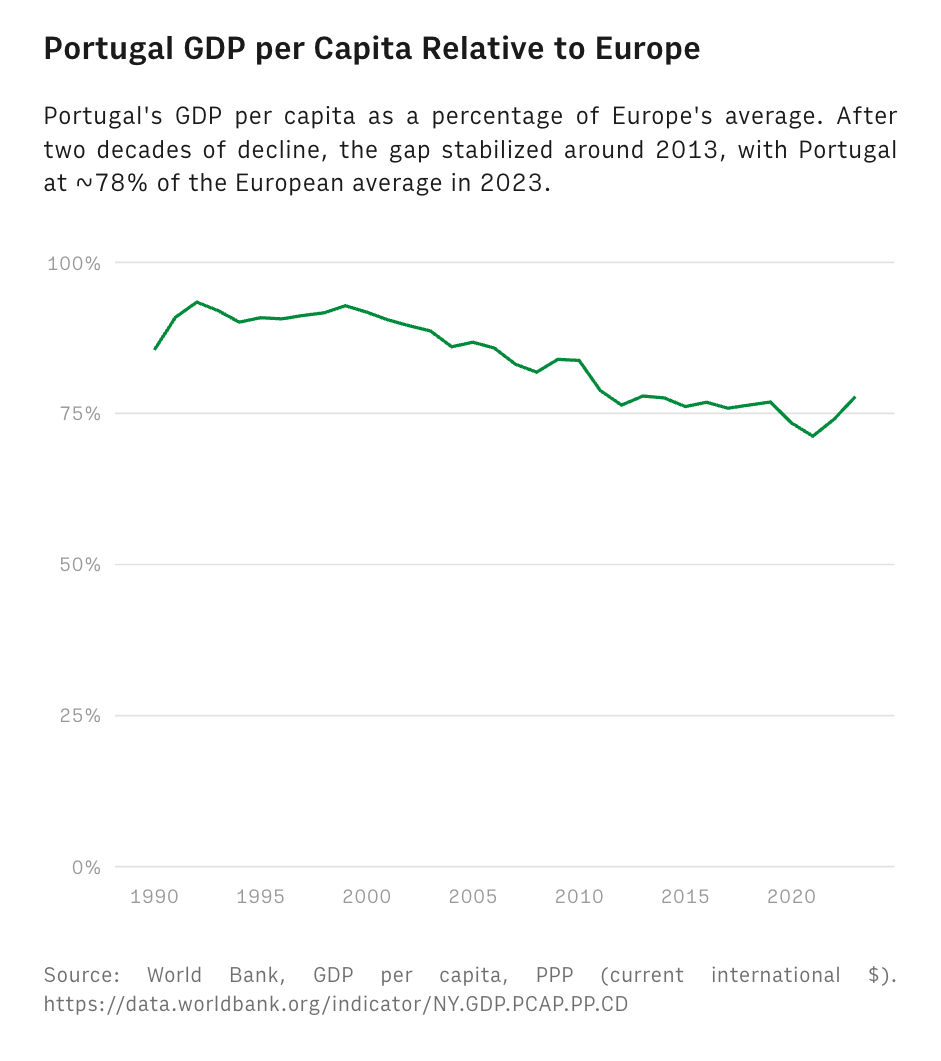

Unlike earlier chapters, the tenth does not apply the same quantitative rigor. Present-day analysis is obviously more challenging, since we lack the benefit of historical hindsight, but the argument would have benefited from comparative data on other major recipients of EU funds—like Poland or Romania—both of which have seen some of Europe’s strongest GDP per capita growth in recent years. Additionally, statistics show that Portugal’s GDP per capita relative to the Europe average has actually remained fairly steady at around 79% over the past decade, which complicates the claims of divergence (source).

Bottom Line

I learned a great deal about Portugal’s economic history—indeed, its general history—by reading As Causas do Atraso Português. The first nine chapters offer a provocative, well-researched, and eye-opening explanation for the country’s economic decline. Palma’s prose is accessible and relatively free of technical jargon, though he does circle back to the same arguments and examples repeatedly. Even so, the data and historical anecdotes consistently hold the reader’s attention.

And while I was less enthusiastic about the last chapter’s theoretical leap, it does not diminish my overall assessment of the book. If you are Portuguese—or can read Portuguese—and want to learn about our (gold) rich economic history, As Causas do Atraso Português is a must-read.

Further learning

- Buy the book

- Download the spreadsheet with data analysis to pair with the book.